An introduction to the Nature Restoration Law

9 August 2023

Meet the Free Flow Champion: Marcy Hamilton

20 September 2023Lisa Hollingsworth-Segedy is the director of River Restoration at American Rivers. She is an expert in the river restoration field and has been leading the Oakland Dam removal on the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania. We had the opportunity to interview Lisa about the Oakland Dam removal and dive deeper into how it all began and what her team has accomplished so far.

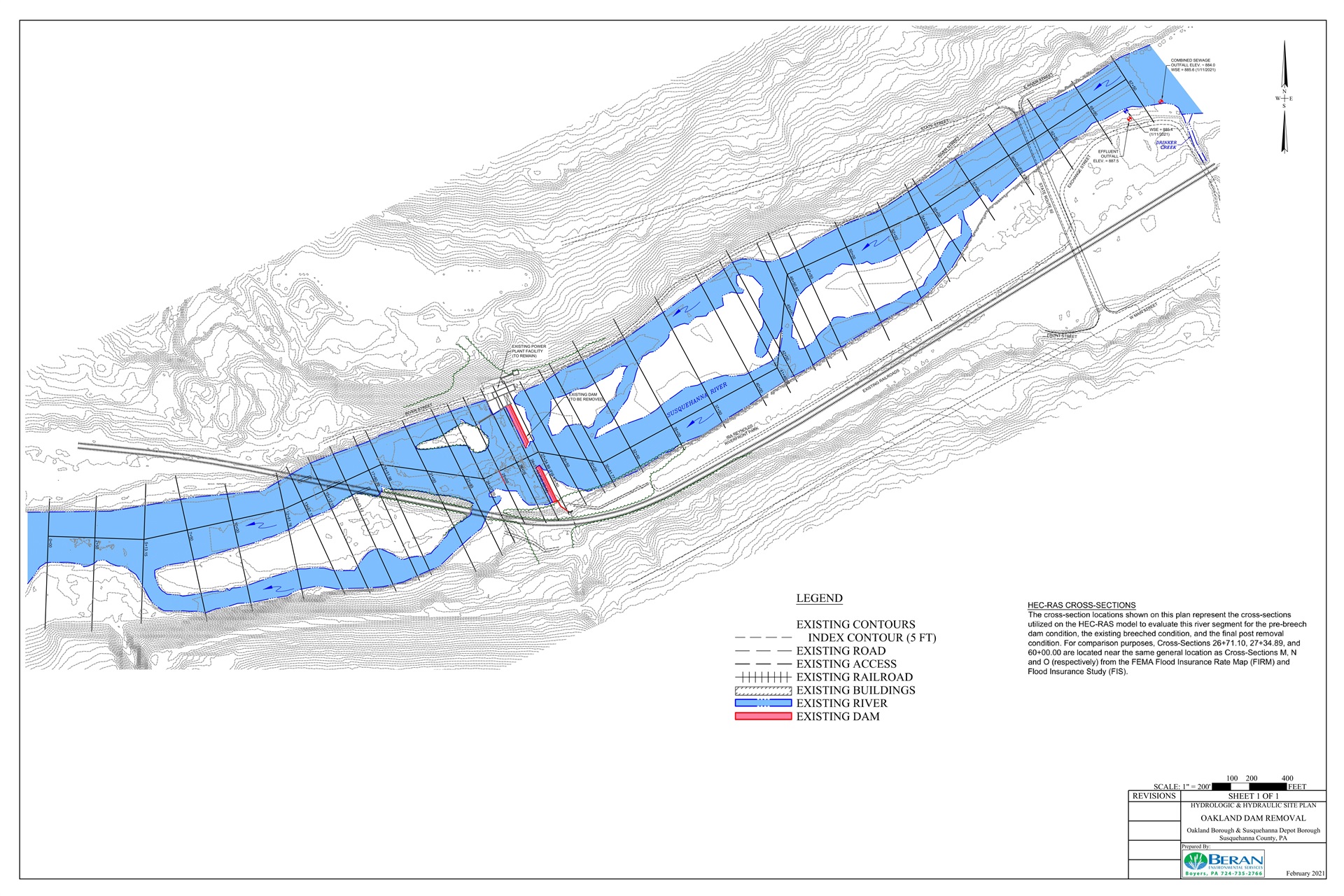

The Oakland Dam, located on the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania, has been a source of major safety hazards and has contributed to the deterioration of the river's health. Lisa and her team embarked on the ambitious project to remove this dangerous and obsolete hydropower dam that was abandoned in the 2000s due to a breach in the centre of the dam. The removal of the Oakland Dam started on July 25, 2023, and it represents the largest dam removal project in Pennsylvania to date.

What inspired the Oakland Dam removal?

[Lisa] Shortly after I joined the staff in 2008, the Pennsylvania habitat restoration lead at our US Fish & Wildlife Service reached out to me and asked me to consider taking on Oakland Dam as a removal project because it was partially breached. In other words, it was a failed dam and a significant velocity barrier for riverine sportfish as well as migratory species. This proved to be a difficult project because at that time the dam had an exemption from Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, our US hydropower regulatory agency. An exemption means that the dam was generating power prior to the creation of FERC so it was “grandfathered”. As long as the dam fell under the authority of FERC, the state dam safety agency had no jurisdiction so there was nothing they could do to address the dam failure.

Were there any challenges along the way and how were those overcome?

[Lisa] Many! First was that situation where FERC was taking no action regarding the dam failure, and state dam safety had no jurisdiction to do anything about it. Second, in 2014, FERC withdrew the exemption because the dam’s use for hydropower had been abandoned for more than 30 years (due to the dam failure, there was no pool; the turbine and other generating machinery were obsolete; there was not enough power being generated to create a profit stream from which monies could be used to refurbish the dam and the power station). For the next 3 years, three different hydropower companies put in a permit on this dam, which is a 12-month exploratory period to determine if power generation is feasible. Of course, all three of these efforts resulted in findings that generating hydropower at Oakland wasn’t feasible due to the magnitude of repairs that would be required compared to the return on investment. Finally, in 2017, FERC refused additional permits, and that gave Pennsylvania Dam Safety jurisdiction over this failed dam at last. 2017 was also the year that Pennsylvania designated this reach of the Susquehanna River as a Pennsylvania Water Trail, which means that the state started actively promoting the river as a place for water recreation. This was just the push we needed to highlight the danger to paddlers that the breached dam posed—a dangerous hydraulic with submerged, protruding rebar, right in the middle of a place where people were being invited to come get in the river. At that point, it was fairly easy to get the community on board for dam removal. In Pennsylvania (PA), a dam owner is liable for any injuries or deaths resulting from their dam. When the dam fell under the jurisdiction of PA Dam Safety, the community owning the dam realized they didn’t want to bear the liability for a failed dam on a water trail.

Another big challenge was that I didn’t have any existing resources with which to cultivate this project because of its geographic location. American Rivers is a nonprofit organization; we rely on foundation support for identifying and cultivating dam removal projects in geographies where foundations are willing to invest. Oakland Dam is in the headwaters of the Chesapeake Bay watershed, and I had no foundation funder in that area. So, I worked on this project on my own time around my other funded work to get it started. My first funder was River Bounty, the hydropower operating entity, which provided $15,000 in seed money to cover my time to fundraise and coordinate the project. I used that to eventually raise about $425,000 for dam removal construction.

An additional challenge is the size of this dam—the longest dam removal in Pennsylvania to date. Not the tallest—Oakland is only 16 feet (4.9 m) high, and the tallest dam in PA removed to date was 37 feet (11 m). Oakland is about 800 feet long (244 m), with the breached section in the centre being about 150 feet long (46 m). Note that the breach is only the dam breast; the footer is still mostly intact. Because of the anticipated deconstruction budget, it took me from late 2018 to early 2023 to secure funding from six separate sources to fund dam deconstruction.

Yet another challenge is the visibility of this project. It’s not the first dam removed from a PA Water Trail, but it is the first dam to be removed from the mainstem Susquehanna River, so that creates some visibility. The number of funders involved in this project has created a lot of interest in the project, and I’ve been giving dam removal tours at the rate of 1-2 per week during construction for agencies that have invested in this project.

The final challenge is the actual dam breach. We are demolishing the river left portion of the dam and using the rubble to build a causeway across the breached section to access the river right portion of the dam for demolition, because there is no safe access to the dam from the river right bank (extremely steep, no room to cut a ramp). Last week, our causeway was just a few feet shy of the river right section of the dam, but this week’s heavy rains have caused some of our causeways to wash away. We are now waiting for the water level to drop so we can repair our causeway and get busy demolishing the right section of the dam. Download the two blueprints of the dam removal plan (1 & 2).

Update: after several high-flow events, we made a field revision and found a riverbank access route to the dam’s right abutment. We are now demolishing the dam’s right limb via that access. Eventually, we will walk the machinery back across the river on a causeway built of rubble, removing it as we go to repurpose it for streambank restoration on the river’s left bank.

How has the local community responded to the removal?

[Lisa] There are still a small number of people who want their hydropower back. There are a few that see American Rivers as a thief stealing their history because they grew up fishing on the dam. But most people have grasped how dangerous the breached dam is to paddlers and anglers, and they are happy to see it go. There’s a lot of local support for expanded recreation tourism because this area of the state has lost a lot of railroad and mining jobs over the past few decades. They see the new water trail without the dam going hand in hand with a recent rails-to-trails project and the recent brownfield restoration that created a beautiful, well-loved park on the river near the dam, and they realize that there are some great eco-tourism entrepreneurship opportunities at the junction of these developments.

What fish species, or other species/ecosystems have benefited?

[Lisa] Dam removal construction is still ongoing, but when the river is reconnected in a few weeks, we will reconnect large river habitat for riverine sportfish such as smallmouth bass, muskellunge, walleye, and perch, as well as migratory species such as shad, herring, and American eel (all of which are being trapped and hauled around large dams closer to the mouth of the Susquehanna River as part of a settlement for those dams’ continued operation). In addition, small-bodied riverine fish such as darters, shiners, and dace are mussel fish-host species for several species of freshwater mussels in this part of the Susquehanna basin.

How many river kilometers/miles have been opened/reconnected thanks to the removal?

[Lisa] The completed dam removal will reconnect 250 miles (402 km) of large river and headwaters habitat, which is the largest aquatic habitat reconnection to date in Pennsylvania.

What is one thing you/the team/community are most proud of about this removal?

[Lisa] I’m proud to finally be in dam removal construction after 15 years of working on this project. I’m also proud that it is the first mainstem Susquehanna River dam removal (and it won’t be the last!) and that I was able to assemble the funding from sources that are previously untapped by American Rivers (state agency funds dedicated to water trail improvement). The local residents I’ve talked to are grateful to get rid of the significant safety hazard that the failed dam is posing to people using the water trail. In fact, once the dam is out, now vacant land next to the dam is planned to be developed for tent camping and a new canoe/kayak launch for people who are doing multi-day water trail excursions.